You're free to speculate on how and why this happens, and as with any serious cultural undertaking, there are too many people and too many motivations involved to assume this is a mono-causal phenomenon. Nonetheless, I partially attribute these revivals to the simple fact that the participants in the 'original' culture, having aged enough in the span of 20 years to become cultural taste-makers in their own right, seize on this opportunity to make the relevant culture of their youth into a relevant culture for all time. Now ensconced within the A&R departments of record labels, or working as arts reviewers for the local weekly paper, or as radio DJs, etc., these 'sleeper agents' may initially pretend that they have no personal interest in seeing their youth culturally immortalized, and that they merely see its cultural products as one item among many for public consideration. As time goes on, though, they may have an equally feigned "revelation" stemming from the "spontaneous" re-discovery of some buried cultural treasure, and will engage inmissionary efforts to convince the new generation that "the new thing" is in fact an old thing that never really earned the full recognition and acclaim that it should have.

WaxTrax Flashba(x)

Yet not every musical genre makes the cut for a full-blown critical re-animation. Some movements come and go without ever having been embraced by the masses, or having been properly conceptualized to begin with, and so one cannot revive that which was never known to exist in the first place. Also, for cultures that wish to set themselves against the mainstream, constant efforts are made to elude classification, even if this is done at the cost of limiting the culture's membership. As Agnes Jasper writes, "as soon as criteria for sub-cultural identity are conceptualised, they can be copied by outsiders, and this should preferably be avoided."[i]

One culture that originally met such criteria is the industrial dance music whose innovative heyday was roughly from the years 1985-1991, whose showcase label was Jim Nash and Dannie Flesher's WaxTrax![ii], and whose geographical epicenter in the U.S. was Chicago, Illinois. That final statement does need some qualification, though: if compared to the number of, say, original Detroit Techno producers who claimed Detroit as a place of residence, the number of WaxTrax recording artists resident in Chicago were not numerous enough for this style of music to be properly called a "Chicago scene." In fact, Nash and Flesher had relocated from Denver, and originally started their enterprise in order to license European acts on labels like Play It Again Sam or Antler / Subway for American distribution. However, the label's Chicago base, along with the local infrastructure of studios (Chicago Trax) and live venues (Medusa's, Cabaret Metro) guaranteed that it was a regular port of call for talent as far afield as Brussels. This sense of international relevance certainly assisted to energize a local fanbase, and to bring in plenty of curious new recruits.

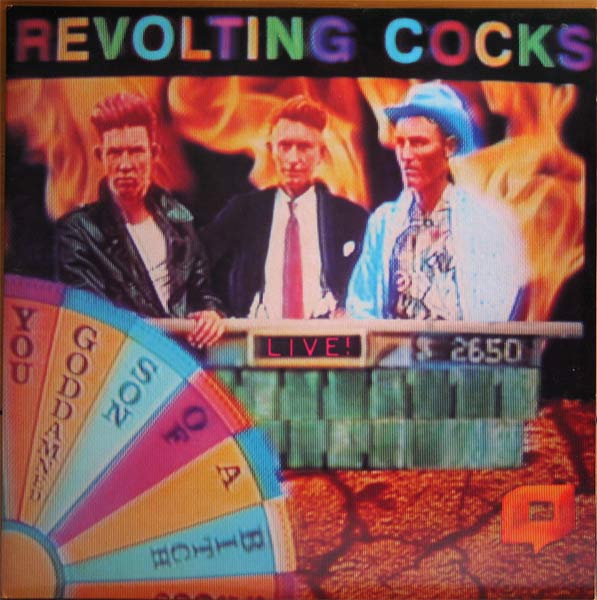

Though some will disagree with my assessment (particularly those with access to record company sales figures, which I don't have at my disposal), I submit that the most representative and popular bands of that scene were Meat Beat Manifesto, My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult [hereinafter 'TKK'], KMFDM, Front 242, Skinny Puppy and the personalities associated with the Ministry / Revolting Cocks projects. Not all these artists were the exclusive property of WaxTrax: Skinny Puppy's most enduring material was done for the Canadian indie Nettwerk, and Ministry's most popular work was recorded for the American major label Sire, though this did not prevent the Ministry writing team of Al Jourgensen and Paul Barker from conjuring an impressive number of aliases (PTP, 1000 Homo DJs, Pailhead etc.) whenever they wanted to skirt their major label contractual obligations and grace WaxTrax with a new 12" release. Personalities from the original wave of British Industrial music (e.g. Psychic TV, Cabaret Voltaire, Chris & Cosey, Clock DVA, Coil) or simply from the more confrontational fringes of electronic music (Laibach, Controlled Bleeding, Jim Thirwell's many name variations on the 'Foetus' brand) were also well served by the WaxTrax scene infrastructure when they chose to transition from anarchic experimentalism to more dance-oriented forms.

Storming the Studio

In terms of direct musical precedents, this style took its cues from the fitness fetishism of Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft (Nitzer Ebb's That Total Age), the urban paranoia of Mark Stewart (Ministry's Twitch), and the mixed-media overload of Throbbing Gristle (Skinny Puppy's VIVIsectVI). UK acid house and the Belgian 'New Beat' scene of the late 1980s featured some structural similarities with the WaxTrax-associated style, although the latter always took greater liberties with distorted vocals and percussion, and utilized more variety in keys and time signatures. Loud guitars would eventually become a prominent element of the mix as well, with the clipped and meticulous rhythmic style of Wire and Killing Joke providing much of the blueprint for the six-string's deployment within industrial dance music - by 1990, the thick "chunk" riffing of thrash metal was also a staple of the band KMFDM, who originally relied upon sampled phrases (their 1990 club hit 'Godlike' cribs the same Slayer riff featured in Public Enemy's 'She Watch Channel Zero') and later employed live guitarists. Though this feature originally had a knowingly over-the-top, faux 'bad ass' feel to it, countless latter-day bands would adopt metal riffing as a signifier of deadly seriousness.

The studio-as-instrument concept, previously put to use by pioneers like Adrian Sherwood and Lee "Scratch" Perry, was also an indisputable part of the genre's musical approach, with the digital sampler taking pride of place within this active environment. Whereas much electronic dance music of the 1980s could be capably built up from synthesizer sequences and beats alone, industrial dance tracks required a sample-based collage technique to fully achieve their alternatingly dystopian and euphoric feel. An album title like Meat Beat Manifesto's Storm The Studio encapsulated the genre's approach to sampling as well as anything, with a staggeringly detailed mosaic of soundbites giving that album its unique controlled chaos, and with sampled dialogue playing just as important a communicative and emotive role as the band members' own vocal turns. Again showing some parallels with other contemporaneous genres based on studio experimentation, industrial dance music shared hip-hop's fondness for making rhythmic loops of James Brown and other assorted funksters, while also leaning heavily upon 'ethnic' samples from globally dispersed aboriginal cultures. All of this was then set in stark relief against a sampled 'sonic opposition' defined by its self-righteousness and arrogance - the outbursts of religious demagogues, sneers of disapproval from indignant housewives, and imperious harangues of prohibitionists all hovered ominously above the songs' slamming-door beats and insistent synth-bass sequences.

If all of this sounds like a confusingly malleable mix of sonic features, then the ideals animating the music were even more likely to keep 'outsiders' guessing and to make the genre's conceptualization more difficult. Early, non-industrial releases on WaxTrax included a single from John Waters film mainstay Divine, a fact that tells us a lot about the label's enthusiastic embrace of American-style irreverence and its fascination with junk culture. This caused a novel frisson with the music's stereotypically Continental ethic of 'technical precision,' and is especially audible on the TKK albums and singles recorded for WaxTrax.

Politically, the bands and their fans were not easy to slot into a purely left wing or right wing orientation, and - as Stephen Lee notes - they were mostly guided by a "vague ideological agenda of difference"[iii] which was maybe closest to the American-style anarcho-libertarian attitudes of Al Jourgenson's admitted mentors, author William Burroughs and psychedelic activist Timothy Leary. Outside of obviously leftist agit-prop groups like Consolidated (who never recorded for WaxTrax), the scene was mainly a convergence point for, as Lee suggests, lifestyle affectations that had been marginalized by the mainstream culture of the day. A general, ecumenical disdain for social control and coercion was a negotiation point that may have alienated those otherwise affiliated with specific parties or single issues,[iv] yet any political program more clearly stated than this would have made the scene less attractive to its fans, who did seem to enjoy it precisely because it was a petri dish for all manifestations of "difference." It has to be said, though, that along with vague individualist anarchism, typified by a strongly voiced disdain for drug laws and sexually restrictive religious morality, the scene also projected a collectivist concern for the survival of all sentient life, as exemplified by Meat Beat Manifesto's veganism or Skinny Puppy's dire ecological prognoses. Harsh lyrical broadsides against animal cruelty seemingly interpreted this cruelty as the logical extension of coercive bullying directed at non-normative humans.

Ain't it Dead Yet?

The fate of industrial dance and 'hardbeat' artists in the post-WaxTrax era has hardly been uniform, either, with some suffering the fate of increased obscurity and others broadening their creative range far beyond the limitations of industrial dance. Among the latter is vocalist Chris Connelly, who had already begun a career as a potent and eloquent singer-songwriter while still active as an industrial scream machine, and whose recent releases include works of free-form electronics and a volume of prose. Ministry drummer Bill Rieflin has contributed to releases and live appearances from Swans, Robyn Hitchcock and R.E.M. Bassist Paul Barker remains busy with production work and partial ownership of Malekko Heavy Industry Corporation, a boutique manufacturer of effect pedals and synthesizer modules. As to the WaxTrax label itself, it did not exactly die an ignominious death immediately after industrial dance fell out of critical favor: always a label that relied heavily upon licensing of European labels' rosters, its mid-1990s licensing agreement with the notorious U.K. label Warp again put it on the leading edge of electronic dance music. The Warp label's Artificial Intelligence compilations, along with key releases by Autechre, The Black Dog and Richard James [as Polygon Window] provided more than a few North Americans with their first taste of an emerging field of electronic music meant to simultaneously satisfy the needs for physical release and intense contemplation.

Musical genres themselves may die out or fade away, but, owing to some sort of Law of the Preservation of Musical Energy, it seems as if there are a limited number of eternally recurring musical energies that simply become re-invigorated by changing social circumstances: the names and faces attached to each incarnation may melt away over time, but the attitudes themselves persist. In fact, we don't even have to step outside the city limits of Chicago to see where this might be the case. Although the Windy City is famous for being the site of the ritual slaying of disco - i.e. Steve Dahl's notorious 1979 Disco Demolition Night in Comiskey Park, at which a sacrificial blaze erupted from thousands of disco LPs destroyed in the middle of the playing field - it is simultaneously one of the key sites of disco's rebirth (some might merely say "re-branding") as House music. Nearly every salient characteristic of House, from the strict 4/4 time signatures to the use of a 'soulful' palette of vocal stylings, is heir apparent to the aesthetics and the social aims of disco.

Nobody seems to understand the nature of recurrent musical energies better that those scene professionals whose job it is to keep a crowd energized, namely club DJs - unlike the rest of the critical community that relies on textual or verbal communications to argue for the merits of a musical style, DJs can argue for those merits with the much more performative practice of re-introducing older tracks into their live sets. So it is maybe unsurprising that some successful cross-fertilization has already happened within the chic circles of international DJ culture, where the impact of WaxTrax-style dance music has been acknowledged from time to time: French DJ and producer Terence Fixmer has fetishized the authoritarian EBM of groups like Nitzer Ebb, both in his own music and in remix compilations for the band itself, the latter of which have also featured Phil Kieran and The Hacker. Photogenic superstar DJ Hell has also commercially released adventurous mixes such as "Electronic Body House Music," which aims at finding some points of continuity - or at least compromise - between the militaristic style of industrial dance acts like Front 242 and more soulful variants of 'tech-house.'

However, the critical community of reviewers, bloggers, and academicians seems much less keen to act as apologists for the brand of dancefloor brutality under discussion here (some academics like Alexei Monroe and Pete Webb are notable exceptions.) Whereas once concert appearances by a group like Ministry rated as a "critics' choice" by Chicago-area journalists, and postmodern cyber-culture critics like Arthur Kroker eagerly namechecked the band in their panic-laden theoretical prose[v], it is almost unthinkable that the same would happen today. Of course, where that band itself is concerned, this state of affairs owes itself to a dramatic shift towards gradually more indistinct and risk-free recordings, and one does not need to be a regular contributor to Wire or Pitchfork Media to find it a medicore brew. As to the entirety of the aggro-industrial scene, though, it is puzzling why they have been given short shrift in the Western, 21st century's relentlessly self-cannibalizing, re-appropriating cultural landscape (especially considering how these characteristics were embedded in the music itself.) I can only offer some speculations as to why this is the case, but hopefully this will get us to the meat of the matter - and, more importantly, to determine if being "passed up" by the re-assessment brigade is really such a bad thing.

Bad Mood Guys?

It would seem that demystification is one of the most important tasks that modern cultural critics can take up. Many music reviewers determine the merit of a given recording or performance solely upon how much demystification it requires of the audience, making criteria like audio fidelity and technical skill subordinate to this. So while industrial music, whether saddled with dance rhythms or not, usually comes under the critical blowtorch for its perceived nihilism or its perceived sociopathic tendencies, it is worse still for the scene that it has never been able to convincingly shake accusations of contrivance, particularly the 'aggro' pose in the music and fashion stylings which was suspected to be a cover for deep-seated insecurity. This is something that Chris Connelly acerbically critiques by claiming Front 242 "had cornered a part of the dancefloor occupied by a lot of people who were too afraid too admit that they were in love with Depeche Mode, and liked to play at soldiers."[vi] The frosty musical atmospheres of certain industrial dance tracks, and the monumental angst exuded by the club-goers were also ripe for comical parodies, with the classic "Dieter's Dance Party" skit from Saturday Night Live effortlessly transforming the narcissism of electro-industrial clubbers into an object of ridicule.

The in-your-face sonic clatter and imposing packaging of industrial dance records have long been out of favor with a critical community that places a higher truth value on audible vulnerability than upon projections of brute strength (and to be honest, I'm perfectly happy if I never see another album cover with a "menacing" skull on the front.) The poorly named culture of Outsider Music[vii] is thus a kind of critical holy grail, defined as it is by artists who are blissfully unaware of their own kitsch stylings and thus impervious to record industry concerns of styling and image. "Positive, redemptive kitsch,"[viii] fueled by artists who have an almost genetic lack of ability to understand current fashions or to ulterior motives for what they do, is posited as one of the weapons of the independent music resistance against a programmatic entertainment industry that centrally plans and directs the careers of all its human assets over a projected, limited timespan.

However, brute strength was never the only card that industrial dance music had to play, and its capacity for poking fun at itself was greater than what non-participants in the scene may have been led to believe. Indeed, self-deflating tendencies in the music and visual presentation were quite common for a while. This could be seen in the singular fashion sense of KMFDM's 6'6" vocalist En Esch, who would mix the stock industrial dress of military surplus and tall black boots with items like colorful polka-dotted leggings or checked golfers' pants. It was certainly audible in the Revolting Cocks releases co-written with Chris Connelly (circa 1988-1993), which he describes as an "incredible collision of technology, toilet humour and dada…it was kind of like Benny Hill and The Terminator rubbing shoulders with Kurt Schwitters."[ix] The Revolting Cocks' cover versions of mawkishly sentimental songs (Olivia Newton-John's "Let's Get Physical" or Rod Stewart's "Da Ya Think I'm Sexy") could be seen as the resolute destruction of a weaker, escapist musical form by a stronger and more realist one, yet the very selection of these songs is also a kind of self-effacement on the covering bands' behalf: the truly humorless "extreme" artist would probably reveal himself as a phony by even knowing that these songs exist. Interestingly, the ironic industrial cover song would become a staple of the scene a few years after the Cocks' pioneering forays, and in the hands of lesser personalities these songs did eventually become a kind of humorless novelty with an increased sense of self-consciousness and missionary "hardness." But here we are getting ahead of ourselves, as the arrival of these lesser personalities is a story all unto itself.

Further Down The Spiral (and Up The Charts)

Much of the blame for the death of the WaxTrax scene has been laid at the staff of that label itself, and the all-too-familiar fate of independent labels whose popularity grows too quickly and unexpected for their limited infrastructure to respond to in a timely manner. As Steven Lee recalls,

When KLF's 'What Time is Love' turned into a huge dance club hit, [Jim] Nash found that creditors refused to help finance any expansion because of the company's poor credit history. As a result, Wax Trax lacked the financial resources to keep up with the demand for the single and therefore missed one of its biggest sales opportunities.[x]

However, these missteps on the part of the WaxTrax label also do not account for the ongoing critical un-acceptance of industrial dance music. In our present era characterized by global digital distribution and quasi-legal downloading of labels' entire back-catalogs, the original releasing entities do not need to be active for the music to continue finding new ears, nor for the sleeper agents to awaken and begin new efforts. As David Hesmondhalgh notes, there is another side effect of expansion more pernicious than what is outlined in Lee's exampled above:

The danger for an independent in 'crossing over' is, in the terms of dance music culture itself, the loss of 'credibility': gaining economic capital in the short-term by having a hit in the national pop singles chart (or even having exposure in the mainstream or rock press) can lead to a disastrous loss of cultural capital for an independent record company (or an artist), affecting long-term sales drastically.[xi]

There is certainly some truth to this: WaxTrax' own lack of preparation for success was not as influential upon the scene's critical demise as the 1994 commercial breakthrough of Nine Inch Nails, an act that had long been hovering on the peripheries of substantial fame. NIN's Trent Reznor was gifted with a vocal repertoire that ranged from sensitive whimper to lacerating shriek, and a programming touch that mirrored that vocal range. More importantly, though, he provided the mass-marketable, charismatic "pinup" icon that had otherwise eluded industry professionals. Armed with looks that were more appealing than the cyber-cowboy grunginess of the Ministry / RevCo gang, and shorn of the troublesome anarchism and eco-disaster scenarios of other notable groups, Reznor was crafted into a special kind of '90s youth culture heartthrob - the angst-ridden "hater of all humanity" who might just be "tamed" by the right caring soul. Though this was a variation on a daydream / fantasy that had been part of American pop culture since at least the days of James Dean, Reznor's variation on these theme was just sharp enough to make this daydream seem exclusive to the kids of the '90s.

This is not to say Reznor was a disposable bubblegum pop star, allowing record company executives to lead him around by the nose ring: his occasional employment of characters like Bob Flanagan and Peter Christopherson showed that he had some knowledge of the performance art and intermedia subcultures that informed the original wave of industrial music, and hinted that he was not a whole cloth fabrication of the industry. Yet his success proved fatal in that it allowed for the aforementioned conceptualization by outsiders to take place: this meant a critical oversimplification of what could be expected from industrial dance music, and to the subsequent scenario in which newer industrial dance bands bought into this oversimplification, finding it more potentially rewarding to cleave close to the NIN formula than to venture down less well-trodden creative paths.

A great irony of this was that the embrace of the NIN formula, which was flawed but certainly complex and eclectic, resulted in a glut of bands and producers who simply saw sonic harshness and bombast as the winning ingredient in that formula, rather than sonic eclecticism. Newer American record labels like Fifth Column and Cleopatra (the latter being even more reliant upon American licensing of European labels than WaxTrax), also helped to present an increasingly compartmentalized scene in which guitar-heavy industrial dance acts were re-christened as "machine rock" and guitar-free industrial dance bands were "electronic body music." As the subgenres multiplied, new label signings arrived who differed from the earlier WaxTrax crop in another crucial aspect: rather than being pan-artistic individuals who 'fell into' industrial dance music as an extension of their other creative activities (e.g. poet, painter and would-be filmmaker Frank "Groovie Mann" Nardiello from TKK), the new 1990s breed appeared to be coming from a strictly musical background, or had intentions limited to the production of music.

Meanwhile, one of the features of the scene that had previously allowed for the excited anticipation of new records - the concept that "'x' band / producer is an 'industrial' version of "y" - became much less prominent, as groups became far more content to cannibalize the back catalog and to limit their cultural points of reference to those already explored within 'industrial' proper. The emphasis shifted away from providing industrial culture takes on diverse cultural phenomena to merely becoming "the next KMFDM," or "the next Front 242" and so on. Jim Thirlwell's ability to re-cast everything from Tom Waits to Lalo Schifrin in an industrial mold, with all the pleasurable unpredictability that came with that process, quickly became an exception rather than the rule. The new post-'crossover' breed began to overtake their forebears in the number of visible releases and in the amount of total press coverage. Post-NIN rock banalities like Filter or Gravity Kills were certainly accorded more airplay on the growing number of "alternative" FM radio stations in the U.S. of the mid-1990s, whose policies demanded that they simply play new material - they were not obligated to provide an educational service by putting the newer sounds in a historical context, and were usually not resourceful enough to go digging for out-of-print WaxTrax 12" records.

The infantilization process of the industrial music in the mid-1990s became a definite problem. This was sped along by the prevalence of industrial tracks on the soundtracks for film adaptations of comic books or video games, specifically the soundtracks to the Mortal Kombat movies. Scene mainstays like Trent Reznor and Martin Atkins lent their compositional skill to music scores for PC games like Quake and Club Dead, and while such crossover into other media was certainly a boon for the performers involved, it was precisely the wrong kind of crossover to make if this aforementioned long-term credibility was to be secured. The scene was increasingly seen by outsiders as a form of insincere, escapist violence rather than as a critical art form in its own right, and the continuing association with video games, film adaptations of video games, etc. added more heft to that critique. This association was seemingly burned into the temporal lobes of the American public forever upon the media coverage of the 1999 Columbine shootings, whose perpetrators were said to have stoked their homicidal urges with a blend of video games and aggressive industrialized rock. It probably did not help matters that more critically acceptable pre-Columbine fare, like Gregg Araki's "irresponsible film" The Living End, liberally featured industrial dance music as the backing for violent (if somewhat tongue-in-cheek) revenge fantasies.

User-unfriendliness

Aggressive dance music of the 21st century has caught up with the classics of the WaxTrax era in terms of groove, sonic punch and atmosphere, although the reduced amount of vocals, mass media sampling, and general narrative quality in these new strains has made it much easier to integrate into DJ sets or to use as a social lubricant at parties. Established techno artists like Regis, Traversable Wormhole and Planetary Assault Systems, along with younger acolytes like Tommy Four Seven and Perc, combine the alluring anonymity of their own genre with the unyielding and disciplined rush of classic industrial dance music, yet this music has an ambiguity of intent and sonic mood that allows for its integration into diverse musical mixes, in a way that prime industrial dance could not have been. Simply put, satisfyingly intense electronic music now exists that has a greater degree of access to a greater number of potential users. Those critics who do come to terms with intense electronic dance music are likely to land upon this style first, rather than something done in a more traditionally 'industrial' vein.

This music is also far less demanding on its enthusiasts in other areas: particularly, the public presentation of said enthusiasts. Industrial fashion could be an expensive undertaking - particularly for those who did not have skill in designing their own clothes, and had to buy ready-made outfits from alternative culture supermarkets like The Alley perched on Chicago's hip Belmont Avenue / Clark Street intersection (a local predecessor to the now ubiquitous 'Hot Topic' chain stores infesting American shopping malls.) Moreover, this fashion could be cumbersome, calling for everything from knee-high 21-eyelet leather boots to high-maintenance hairstyles (even Skinny Puppy, despite their indubitably earnest ecological commitments, once sported mushroom clouds of black hair that must have required gallons of Aqua Net hairspray to hold in place.) The "ideological agenda of difference" endemic to industrial dance music meant that fans were required to easily identify one another on the street, to a degree seldom required by other electronic music genres. Despite being an ostensibly inclusive genre, failure to put srious effort into assembling one's paradoxically "non-conformist" uniform might get them laughed out of industrial themed nights at Chicago venues like Smart Bar or Neo, or ignored altogether by club-goers, or treated with all the suspicion generally accorded to an outsider who has unwittingly stumbled into the inner sanctum of a secret society.

Conclusion

On one hand, I feel that musical revivals or re-assessments can be perfectly healthy, and can be a much-needed counterweight against the culture of planned obsolence in which the only products judged "good" are those which are chronologically very recent. More than ever, instant online access to the entire history of recorded music reminds us that (as per musicologist Frederick Stocken) we live in a "temporal village" as much as a "global village."[xii] By Stocken's reckoning, any form of music that can "move us now" - regardless of where it sits on the musical timeline - "cannot be considered old-fashioned."[xiii] I wholeheartedly concur, and it is fascinating to see people increasingly finding a "sound of their own" that may have existed before their own lifetimes.

However, personal re-assessments of past musical styles, or a relatively spontaneous collective resurgence in interest, have a much different character than planned or directed revivals. In the former cases, the re-discovery of music does not have to be attended by a specific purpose, and can be motivated by little more than excited curiosity and enjoyment. In the case of planned revivals, that enjoyment is secondary to the achievement of an ideological purpose, and this makes the process of "re-discovery" more of a revision or a re-edit. The electroclash fad provides a striking example - its reduction of 1980s synth-pop to a genre in which willful naiveté ruled the roost, and in which the cheeky 'garage electronics' of groups like Delta 5 or Xex were more representative of the genre than the sweeping sci-fi ambitions of Gary Numan or John Foxx, is flagrant dishonesty, easily on a level with Happy Days' nostalgic filtering of the American 1950s. It was a move borne out of critical convenience: for those critics who had already proclaimed the ethical superiority and authenticity of indie rock, only electronic or 'synth' music with a similar character could be acknowledged lest these critics seem inconsistent. The selective exhuming of cultural artifacts from the period was made even more dishonest by the proclamation of "lost classics" that were most likely clever 21st century approximations of an earlier 'garage electronics' sound - but this is a story for another day.

When it is weighed against musical genres that have been maligned for similar reasons, there is really no good explanation as to why the critical community has not looked to the WaxTrax sound circa '85-'91, and used it for yet another in the ongoing series of revisionist revivals. Many critics will point to the surplus of lethally dumb music in that genre, which rode on the coattails of the genuinely innovative and perceptive recordings. Others will single out the 'dark' or anti-social attitudes of certain groups as being inappropriate for any present-day consciousness-raising exercises, along with the supposedly limited demographic appeal of the music. However, critics who take these positions will be hard pressed to explain why the recent academic / critical interest in 1990s black metal should be the subject of symposia and scholastic journals, and why industrial dance music should not. The former has been no freer of poor quality control and ethical failures than the latter, and has certainly not been freer from harboring anti-social attitudes.

If anything, though, the industrial dance exception to the rule of revivalism should be welcomed. This last example shows that the critical community still has a tenuous grasp on how it defines the sacrosanct value of authenticity that is supposedly a prerequisite for good music (and thus for calculated reassessments of older forms.) Given that this community itself is still unable to provide all-encompassing definitions of important concepts like authenticity and kitsch, the responsibility for defining these concepts can easily be handed back to individual listeners. The sorts of committee decisions that lead to perfectly timed 20-year musical revivals, even if led by critics who claim righteous intentions such as authenticity and progressivism, are not strikingly different from similar marketing decisions made by the entertainment conglomerates that remain the apparent enemy of such a critical community. Without a musical discovery process that grows organically and, in the beginning, non-purposively, what we will eventually end up with is a culture of competing untruths, each guilty of their own sins of omission, conflation and misrepresentation. And while dishonesty of intent is possible even within a small group of friends or peers, I still maintain that unsupervised sonic exploration is the best building block for new musical movements.

So we do not need to mourn for any leather-clad WaxTrax warriors left behind in the critical wilderness - their work, and that of any other un-revived genres, will find its way to those who truly do want or need it, and they will know if it is for them whether or not they understand its larger historical relevance or its possible role in future manifestations of avant-garde culture. The real re-animator, in the words of Brion Gysin, knows their music "when they hear it," relying on their own intuitions rather than upon arbitrary temporal markers or sea changes in social mood to tell them what has value in their own lives. They should simply ignore any authorities who claim it "isn't time yet" for a "proper" revival of such tastes, and to perhaps blast the famous TKK sample in their ears: "I know what I experience…and I'm not crazy!"

[i] Agnes Jasper, "'I am Not a Goth!': The Unspoken Morale of Authenticity within the Dutch Gothic Subculture." Etnofoor, Vol. 17, No. 1/2, AUTHENTICITY (2004), pp. 90-115.

[ii] Technically, the exclamation mark here is part of the company's trademarked name, though I will write it here without the exclamation mark for greater ease of reading.

[iii] Stephen Lee, "Re-Examining the Concept of the 'Independent' Record Company: The Case of Wax Trax! Records." Popular Music, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 13-31.

[iv] Al Jourgensen's vocal on the track "Apathy," by 1000 Homo DJs, encapsulates this across-the-board suspicion of authority well: "In the Tory or the Labour camps, well it's the same / Republican, Democrat, well it's still the same to me / Go to Lenin or Marx, it doesn't matter / Starve the people while the rich get fatter / Don't you see they've got us where they want us / Don't you see the enemy here, it's you." This sentiment is voiced in 1988, though, and Jourgensen has since focused his fire more squarely upon American conservative and/or neo-conservative politicians.

[v] "Deeply conversant with the formal compositional strategies of Western music, [William] Gibson has also been infected with the noise of bodies in ruins in hyper-reality, from Severed Head’s City Slab Horror and Ministry’s Land of Rape and Honey to the hard-edged rap of the Jungle Brothers." Arthur Kroker, Spasm: Android Music and Electric Flesh, p. 67. Ctheory Books, Toronto, 1993.

[vi] Chris Connelly, Concrete, Bulletproof, Invisible and Fried: My Life as a Revolting Cock, p. 46. SAF Publishing, London, 2007.

[vii] Please see pp. 308-334 of my book Unofficial Release: Self-Released and Handmade Music in Post-Industrial Society, for reasons why I contest this term.

[viii] Emily I. Dolan, ‘… This Little Ukulele Tells the Truth’: Indie Pop and Kitsch Authenticity." Popular Music Vol. 29 No. 3 (October 2010), pp. 457-469.

[ix] Connelly (2007), p. 207.

[x] Lee (1995.)

[xi] David Hesmondhalgh, "The British Dance Music Industry: A Case Study of Independent Cultural Production." The British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 49, No. 2 (Jun., 1998), pp. 234-251.

[xii] Frederick Stocken, "Musical Post-Modernism without Nostalgia." The Musical Times, Vol. 130, No. 1759 (Sep., 1989), pp. 536-537.

[xiii] Ibid.